I recently started sharing my thoughts on LinkedIn, wouldn’t it be a shame if I don’t share them here as well. No preachy monologues or boring rants, I promise. Consider this more of a blog than an article or a newsletter, as I’ll be sharing snippets from my childhood, the books that captured my heart, the movies that left an impact, and much more. Today, I wish to tell the story of a little girl whose love for stories took her on magical journeys to faraway realms, all beginning with a simple sketch pen.

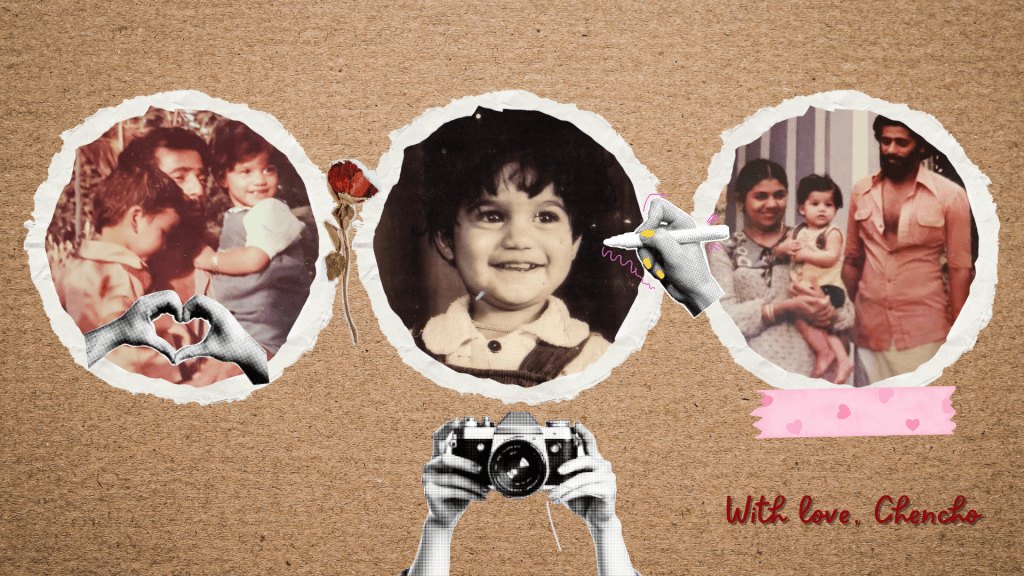

Both my parents were bankers from a generation that stayed in the same career until retirement. They left for work at the crack of dawn and returned by dusk, so as an only child until the age of nine, I spent much time alone. In our quaint town of Pulpally in Wayanad, life unfolded like a scene from a Padmarajan film, with even the smallest moments sparkling with promises. Mornings, however, were far from cinematic, as most days began with humble but warm bowls of Maggi noodles, Bullseye eggs or Upmas served by my mother (Amma), who never had time or inclination for elaborate meals. Even in that unassuming routine, I was as happy as a kid who adored her bowl of Maggi, relishing life’s simplest pleasures.

We were always surrounded by local tribal communities, one of whom was Meenippanichi and her family, who featured prominently in many of my father’s (Abba’s) paintings. They helped around the house and tended the small plot of land by our unique Laurie Becker-style home, which resembled three brick cylinders put together to form a Lego-like structure. The recycled multicoloured bottles affixed to the ceilings lent natural yet vibrant light to the interiors. The three of us even had small circular extensions outside the house for gardening, where we nurtured roses, dahlias, shoe flowers and four o’clock flowers (yes, they bloom exactly at 4 p.m., hence the name). As a child, I saw our home as a whimsical trio of circles, each one a miniature world brimming with its own charm. Air conditioning and even fans were alien to us in Wayanad, as the temperature was always pleasant, never rising above 18 degrees. But that was, of course, in the past. Later, when we moved to Thiruvananthapuram when I was eight years old, we sold that house for a meagre sum.

It was when I was three and still clutching my thumb, a habit that lingered until my father (Abba), the creative genius that he is, devised a clever trick to break it. In those days, every small packet of Maggi came with a free sketch pen. He promised the sketch pen and a story each day if I kept my thumb out of my mouth, and that is when it all began. It was not merely the pen itself that enchanted me, but the fact that it came from Abba, an artist whose creativity shone through in every gesture and brushstroke, and whose stories were far more exciting than my old habit. I never became the next Picasso or even a small-time Frida, but those pens and stories struck a chord, inspiring and encouraging me to try sketching or possibly writing.

Every night, Abba, who honestly should have had his own Netflix special for storytelling, would regale me with tales from the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, the Arabian Nights and even the Bible, sprinkled with anecdotes from his favourite books, his personal adventures, and even his imaginative spin-offs. As I drifted off, I was transported into a world of stories, and the thought of getting a new sketch pen the next day was enough to keep my thumb away. It worked like magic, as I eventually collected all twelve colours, each bringing a fresh, captivating memory. When I began reading on my own, he thoughtfully presented me with abridged, child-friendly versions of these stories.

Even now, when someone asks, “How do you know these rare, almost-extinct stories?” I simply smile. Those storytelling sessions, and the modest sketch pens, shaped me into an avid reader and eventually a writer.

This blog is my tribute to that journey. Sure, reading has taken a backseat these days, with Audible filling in the gaps (oh, modern technology), but I still yearn to relive those moments when a little girl would lose herself in a book, finding both magic and solace in every page.

abilities. Sedunath doles out spaces for Patrick White and

abilities. Sedunath doles out spaces for Patrick White and  to draw inspiration from tradition especially its parallel streams.”

to draw inspiration from tradition especially its parallel streams.”

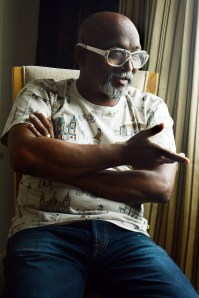

the second year I had an unknown illness which started off as some kind of haemophilia but later on it became something else. I was in coma for a while. This turned my life topsy-turvy as I started imagining that I am having some terminal disease such as cancer. I was taken to doctors all across the state. This lasted for around six years. That is when I started doing theatre,” says Bose. Bose was named after Subhashchadra Bose by his uncle, who was a staunch nationalist. His father’s name Krishnan, which was Bose’s surname, later changed to Krishnamachari adding his father’s profession, asari (achari) to it.

the second year I had an unknown illness which started off as some kind of haemophilia but later on it became something else. I was in coma for a while. This turned my life topsy-turvy as I started imagining that I am having some terminal disease such as cancer. I was taken to doctors all across the state. This lasted for around six years. That is when I started doing theatre,” says Bose. Bose was named after Subhashchadra Bose by his uncle, who was a staunch nationalist. His father’s name Krishnan, which was Bose’s surname, later changed to Krishnamachari adding his father’s profession, asari (achari) to it. In 1985, he received his very first award from the Kerala Lalitha Kala Akademi. That is when he decided to take art seriously. One of his friends from Mumbai told him to join Sir JJ School of Art, where he would get to learn the nuances of art world. He set about to Mumbai in 1985 and wrote the entrance test of Sir JJ School of Art. Bose could only get in the next year due to some internal regional politics. However, he not only passed out with flying colours from JJ but also conducted an exhibition in the college gallery while he was a still a student. “My exhibition was the very first of its kind as the college had never exhibited students’ works before. It had the biggest turnout due to my connections with the external world. I was quite inquisitive so I used to frequent galleries and meet artists. Thus I interacted with people like Akbar Padamsee, and Laxman Shrestha and even visited them at their homes. Padamsee’s house was an adda of filmmakers. There I also got to meet people like Kumar Sahni,” he says. However, Bose’s very first exhibition was held in Kerala Kalapeedom where his dreams took wings. Adoor Gopalakrishnan inaugurated the show there.

In 1985, he received his very first award from the Kerala Lalitha Kala Akademi. That is when he decided to take art seriously. One of his friends from Mumbai told him to join Sir JJ School of Art, where he would get to learn the nuances of art world. He set about to Mumbai in 1985 and wrote the entrance test of Sir JJ School of Art. Bose could only get in the next year due to some internal regional politics. However, he not only passed out with flying colours from JJ but also conducted an exhibition in the college gallery while he was a still a student. “My exhibition was the very first of its kind as the college had never exhibited students’ works before. It had the biggest turnout due to my connections with the external world. I was quite inquisitive so I used to frequent galleries and meet artists. Thus I interacted with people like Akbar Padamsee, and Laxman Shrestha and even visited them at their homes. Padamsee’s house was an adda of filmmakers. There I also got to meet people like Kumar Sahni,” he says. However, Bose’s very first exhibition was held in Kerala Kalapeedom where his dreams took wings. Adoor Gopalakrishnan inaugurated the show there.

they delineate his coming out of shells or cocoons, breaking the barriers. “A sculptor’s life is full of struggles. From the physical exertion to the lack of acceptance, it is not easy to be a sculptor in Kerala. The state is not yet ready to spend money on a sculpture. But I don’t mind that. I have developed an unfathomable attachment with my

they delineate his coming out of shells or cocoons, breaking the barriers. “A sculptor’s life is full of struggles. From the physical exertion to the lack of acceptance, it is not easy to be a sculptor in Kerala. The state is not yet ready to spend money on a sculpture. But I don’t mind that. I have developed an unfathomable attachment with my  works since I have spent months envisioning and creating them,” says Satheesan who spends hours stroking his works to smoothen out their roughness. The 20 sculptures, the result of eight years worth of toil, shows the artist’s creative streak in its fullness. The bronze hooves and horns of the sandstone sheep shine when the rider leads him to eternity. His hand cuddles up a small lamb that looks at the world with its innate innocence. ‘Rider’, Satheesan’s state-award winning sculpture exhibits his strength and versatility in all its glory.

works since I have spent months envisioning and creating them,” says Satheesan who spends hours stroking his works to smoothen out their roughness. The 20 sculptures, the result of eight years worth of toil, shows the artist’s creative streak in its fullness. The bronze hooves and horns of the sandstone sheep shine when the rider leads him to eternity. His hand cuddles up a small lamb that looks at the world with its innate innocence. ‘Rider’, Satheesan’s state-award winning sculpture exhibits his strength and versatility in all its glory. simulate the agony and anguish of those days in sheer perfection.

simulate the agony and anguish of those days in sheer perfection.